Multilingualism and Cognition: Exploring Cognitive Aging with Lifelines Data

How does speaking multiple languages relate to cognitive functioning in later life? Floor van den Berg, linguist and researcher, tackled this question using our Lifelines cohort. “We know multilingualism is cognitively demanding—it’s like a workout for your brain,” Van den Berg explains. “Earlier research often used broad, binary categories that didn’t fully capture the diversity of language experience. Lifelines allowed us to explore this complexity by including people with various multilingual backgrounds.”

A broader definition of language experience

In the study, multilingual experience was defined broadly. Participants didn’t need to actively use another language or identify as multilingual. Speaking a regional regional language, having learned a second language at school, or being raised in a bilingual home were all included. This inclusive approach allowed the team to capture a wide spectrum of linguistic backgrounds.

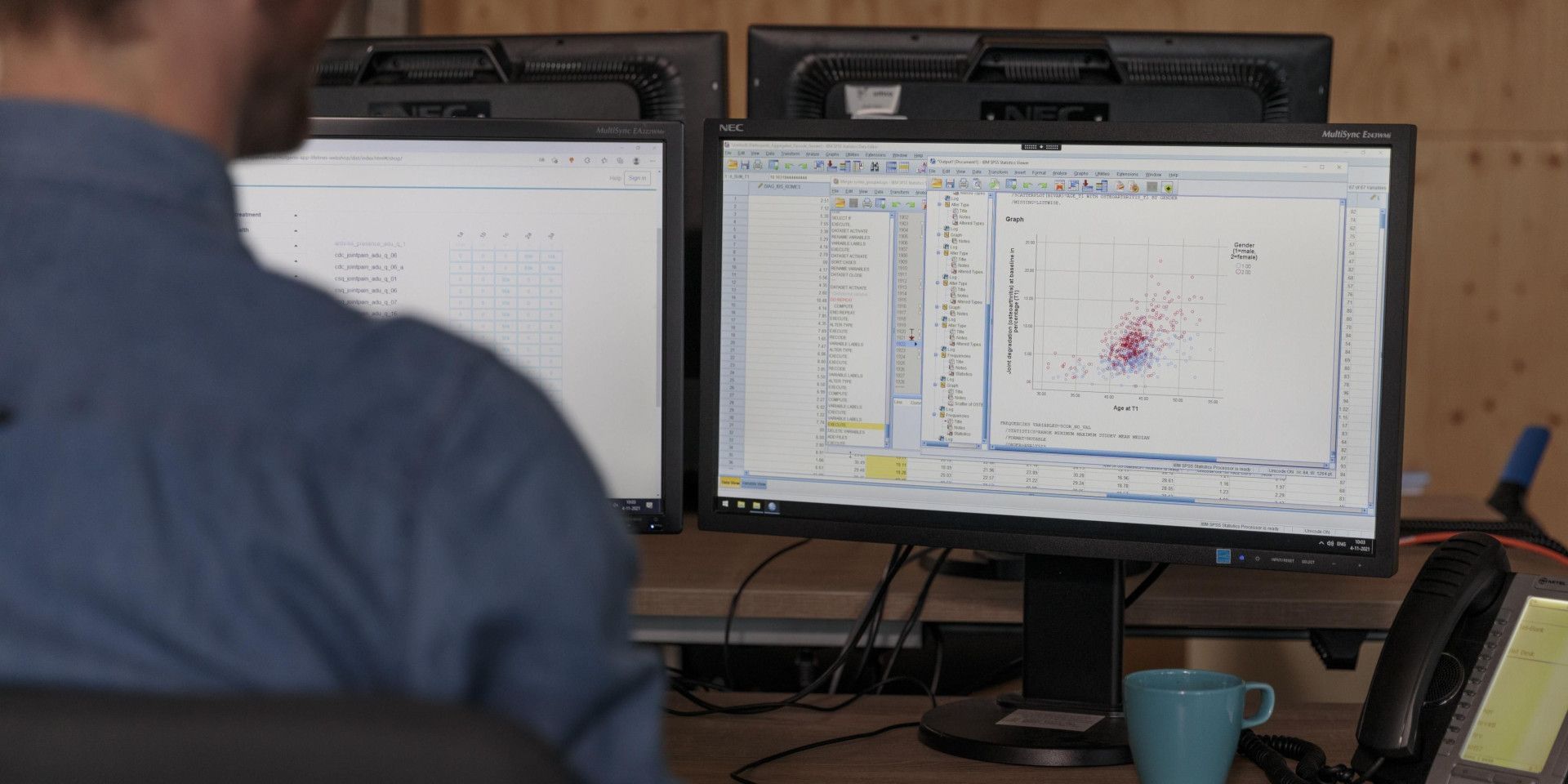

Measuring cognitive functioning with cogstate

To assess cognitive functioning, the study used the Cogstate battery, focusing on processing speed, attention, working memory, and recognition memory. “There’s an ongoing debate about which cognitive processes are most affected by multilingualism. Current frameworks posit that attention control, in particular, plays a key role.”

Key findings: More languages, sharper minds

While the findings don't establish a causal relationship, a clear trend emerged: the more languages a person had learned over their lifetime, the better they performed on the cognitive tasks. Surprisingly, learning a second language later in life seemed to be associated with better attention. One possible explanation is that it requires more attention to keep the first language and languages acquired later apart in the mind; juggling these languages regularly may thereby ‘train’ your attentional skills over time.

The role of education and socioeconomic status

The study also accounted for variables such as education level and socioeconomic status (SES). “We know higher education correlates with better cognitive performance. SES had a smaller and more variable effect, but it’s still something to consider, especially in lifestyle-related studies,” Van den Berg notes.

Contributions to cognitive reserve research

So how does this contribute to our understanding of cognitive reserve and brain aging? “Our findings show that multilingualism is a nuanced experience and should be studied as such. By including people who speak more than two languages, and capturing varied types of language experience, we add to the growing evidence that speaking multiple languages supports cognitive health in some cases.”

The strength of Lifelines data

Lifelines proved to be a powerful data source, offering both scale and diversity. Still, Van den Berg highlights some challenges, like limited granularity in certain language-use questions. Nevertheless, the richness of the dataset made it possible to explore complex interactions between life experiences and cognitive outcomes in a real-world setting.

Toward a deeper understanding of brain health

This research opens new doors for investigating cognitive resilience in aging populations. “We hope these insights inspire more interdisciplinary studies,” Van den Berg says. “If we can better understand how everyday experiences like multilingualism impact brain health, we can develop more targeted strategies to promote healthy aging in society.”